Welcome to the April A to Z Blog Challenge! My theme this year is the Botany of the Realms of Imagination, in which I share a selection of the magical plants of folklore, fairy tale, and fantasy. If you’re just arriving, you’re obviously a little late to the party, but you can find out all about the A to Z Challenge here.

For Z we’ll start with the lotus tree, which is not to be confused with the water lotus plant, for which reason I’m filing it under Z for Ziziphus lotus, that being the Latin name of a real tree hypothesized to be the basis of the myth, and therefore named for it. The lotus tree grows on an island, and its fruit is sweet and delicious. However, whoever eats the fruit and flowers forgets their friends, families, and home. Lotus-eaters fall into a sort of stupor of idleness and apathy in which they no longer care about anything except eating more of the lotus. Obviously this is a magical plant, but (as usual) people have tried to assign its identity to a real plant. There are a number of possibilities, but of course I’ve chosen to go with Ziziphus because it starts with Z.

Zaqqum is another tree with fruit you don’t want to eat — although you may not have a choice! The Zaqqum grows from the depths of hell in Islamic cosmology. Its fruits are shaped like the heads of devils, and the tormented sinners are forced to eat these fruits and be torn apart inside by them. An interesting twist is the idea that the fruits are the growth of the seeds of sin planted by the evil-doers during their lives. I don’t even need to wait until the end of this post to point out that the moral of Zaqqum is not to sow seeds of evil!

The Zieba tree sounds like it could be slightly related to the lotus tree. According to the internet, “No study of fabulous plants would be complete without mention of the Zieba tree, a huge, shingle-barked growth that supported in its lower branches a nest of bare bosomed men & women. Like all those who choose to believe in the tales of these incredible plants, the humans reposing in the Zieba tree spend their days sitting exalted in fantasy, contemplating in wonder all things seen and unseen.” But that’s just the beginning of the story, as far as I’m concerned, and the moral of the Zieba tree is not to believe everything you read on the internet!

But what about the story of the people who spend their days dreaming in fantasy? I can’t find any indication that this 1676 book said any such thing. It’s written in seventeenth century German printed in Fraktur, and while my seventeenth-century German is weak, my Fraktur is even weaker. Nevertheless, I can make out enough to feel confident about a couple of interesting points.

1. In the text the tree is not called Zieba, but Zeiba, which is cognate with ceiba, aka kapok, which, if you recall, is the mundane identity of ya’axché back at Y.

2. The text is all about how the Zeiba tree grows its cotton and how the people of those lands use the cotton. Nothing fantastical at all. I wondered whether perhaps the people shown in the picture were simply harvesting kapok?

3. While point 2 might be plausible, the text never says anything about people climbing the tree to collect the soft fibers, nor does it give any explanation at all of the picture and what, exactly, it might be illustrating. The text and the engraving really have only two points of connection. One is the approximate name of the tree: Zieba/Zeiba. The other is that the engraving labels the tree “15 fathoms thick,” while the text includes the fact that “The thickness of this tree is said to be such that hardly 15 people can surround it.” The word “fathom” (Klafter) is very close to the word “surround” (umklaftern). So it looks pretty clear that whoever made the engraving had done a very careless reading of the text they were assigned to illustrate, and whoever published it had done a very careless proofing job, so that there’s a little garbling between the text vs the picture.

Okay, but none of this gets us any closer to explaining where we got that original story about the “mythical Zieba tree” and its fantasy-nesting people. So finally I managed to get a copy of the 1974 book to find out exactly what Mr Emboden says. Oddly, he asks of Herr Vielheuern in 1676, “What might have engendered in the author the notion of a Zieba tree in which humans sit like fledglings awaiting the day of flight?” One might ask the same question of Emboden, since Vielheuern never seems to have had any such notion at all. In fact, the story seems to have been made up out of whole cloth by Emboden, with a little suggestion from a careless anonymous engraver. This leads me to a few possibilities.

1. In his acknowledgments Emboden thanks the man who sent him the engraving of the Zieba tree, so one possibility is that Emboden never saw the text of the book at all, and just made up his own explanation of the mysterious illustration.

2. Emboden notes that the very long title of the 1676 book lists all the various foreign materials and species and ends with “und davon kommt” which he blithely translates as “and whatever else happens to come along!” First of all, the title ends “und was davon kommt,” but more importantly, I translate this as Minerals, Plants, Animals “and what [materials] come from them.” (Which is in fact exactly what Vielheuern did describe in the case of the Zeiba tree.) So the second possibility is that Emboden saw the text of the book but knows even less German than I do, and made up for his deficiencies with imagination and overconfidence.

3. The third possibility is that Emboden was perpetrating a deliberate hoax. He says “Who among us would not like to encounter a Zieba tree,” and I wonder whether that was a little hint that he was just giving people what he thought they wanted in a popular science book for the masses.

But regardless of which explanation you choose, and regardless of the fact that I quite enjoy this mythical Zieba tree as fiction, I am honestly appalled by this lack of respect for the most basic scholarly standards coming from a senior curator of botany, professor of biology, and lecturer in ethnobotany who supposedly had a distinguished academic career! For shame!

Well, here we are at the end of the alphabet and the end of the April A to Z Blog Challenge. I bet you didn’t expect Z to be the longest post of all, or for a jolly little romp through a magical garden to turn into a scathing exposé of academic malfeasance! I didn’t expect it myself. But don’t worry, we can go ahead and wrap up without further ado; since I already gave you two morals, all that’s left is the gardening tip of the day: be careful that you plant only what you actually want to grow, for as you sow, so shall ye reap. Oops, I guess I just had to squeeze in one last moral.

The final question of the A to Z Challenge always has to be: what was your favorite magical plant? Or if you prefer, what’s your favorite non-magical plant?

[Pictures: Ziziphus lotus, hand colored wood engraving from De Materia Medica, 1555 (Image from Library of Congress);

Zaqqum, illustration by Homa, 2012 (Image from Wikimedia Commons);

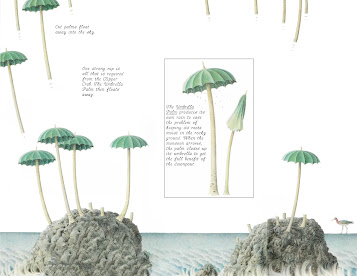

Zieba, engraving from Gründliche Beschreibung fremder Materialien by Christoph Vielheuer, 1676 (Image from Biodiversity Heritage Library);

Zeiba/Ceiba tree, photographs by AEGNydam, 2023.]

.jpg)